CHAPTER TWO

The atmosphere in the apartment is the inverse of the rigid, bureaucratic geometry of the morning. Here, the edges are softened by the scent of ripening fruit and the nectar of the flowers. The light from the Turramurra balcony doesn’t glare; it whispers. Kandace Springs fills the room, her voice like liquid velvet, each piano note a drop of gentle rain that mirrors Michael’s internal state—tender, melancholic, but clean.

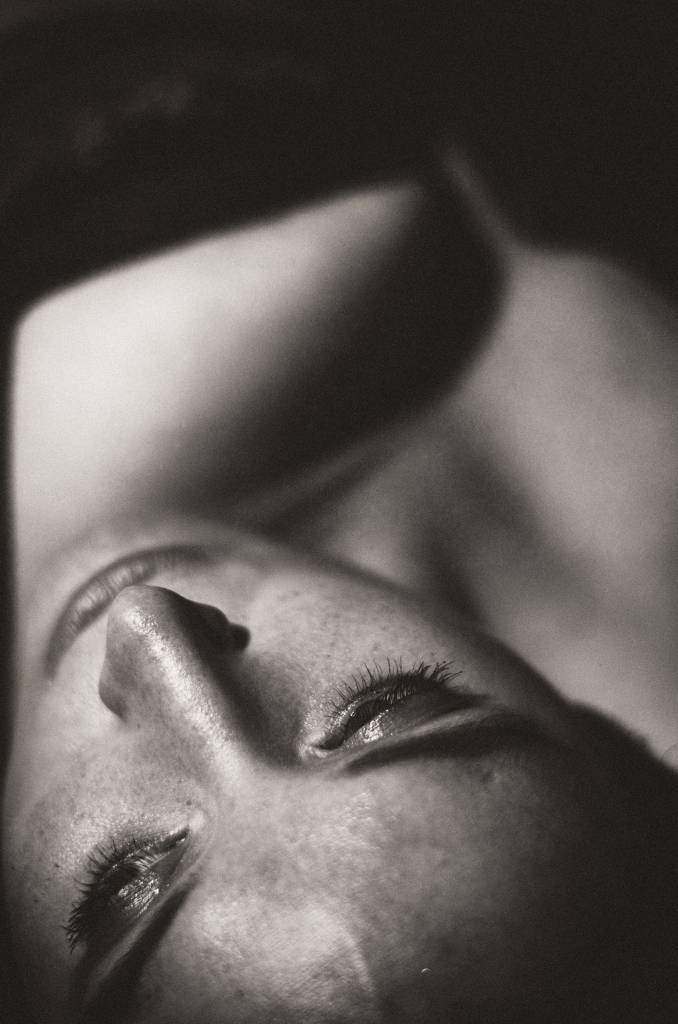

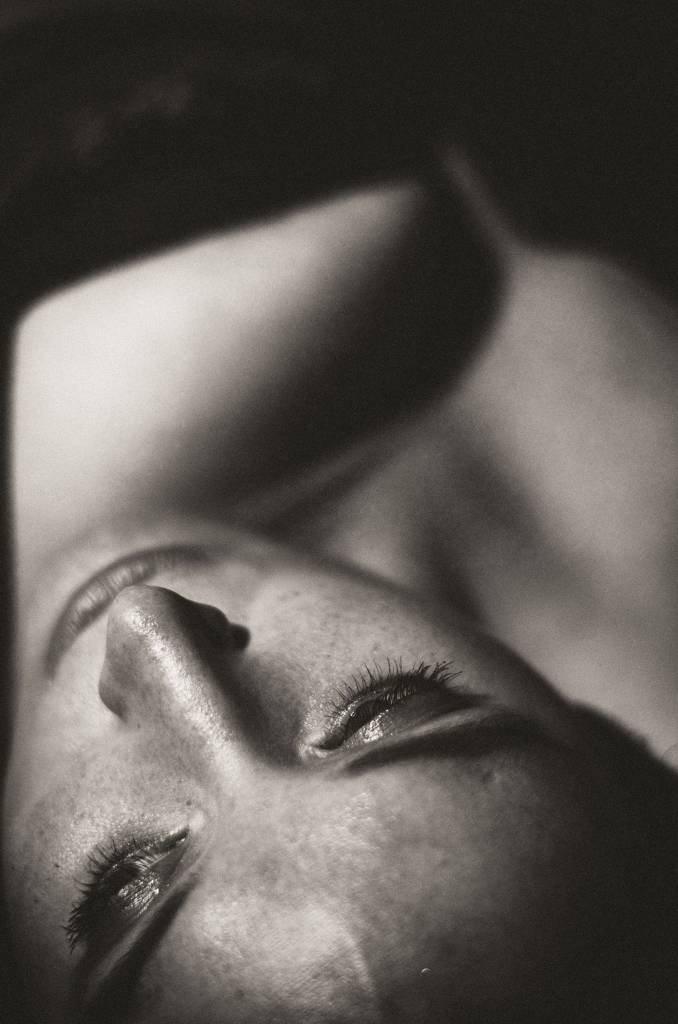

Michael does not sit at the table. He lies down on the cool floor facing the flowers, the fruits, and the light that caresses his eyes.

Michael: “I am sorry. I did not mean to hurt her; I wanted to save her. She was in pain, she was screaming for love, and I had to tell her the truth to free her. She is better than most people; she can do it, but she needs to let go of the illusion. She needs to forgive.”

Zeus: “She is better than most, Michael. That is why the pain is so sharp. You saw the gold beneath the rust and you tried to scrub it clean with a single touch. You say she needs to forgive. But forgiveness is a death—a death of the victim, a death of the story she uses to protect herself from the world. You tried to free her from a cage she is still using for shelter. You offered her the truth to save her, but the truth is a mirror that shows no mercy. She looked into it, saw the distance she still has to walk, and she chose to close her eyes. You cannot force a heart to wake up just because you have the light.”

Zeus: “She is a good kid, Michael. Her spirit is ancient and capable, but you are looking at the mountain from the summit, while she is still shivering at the base. You say if she never walks, she will never get there. But ‘there’ is a place she hasn’t yet agreed to go. You see her potential, her light, and her strength—you see the woman who can do it. But she is still clinging to the girl who couldn’t. By trying to pull her up the slope, you are becoming part of the gravity she fights against. The more you tell her she is ‘better,’ the more she feels the weight of your expectation. To her, your belief in her is just another standard she is afraid to fail. She can do it, yes. But she must do it because the cage becomes too small, not because the Savior is calling from the outside. You have shown her the sun; now you must trust that the memory of that warmth is enough to make her want to walk out on her own. You have done your part. Now, you must let the silence do hers.”

Michael: “Yes, I told her I loved her not because I wanted a relationship, but because I felt her pain in my heart. The words came out without me weighing them. I probably placed too much weight on her, but that was never my intention.”

Zeus: “The heart has no scales, Michael. It only has depth. When you feel the pain of another as if it were your own, the words don’t pass through the mind—they bypass the filter of the ego and the safety of the ‘rectangles.’ They come out raw. You did not weigh them because you were not negotiating; you were bleeding truth. But you must understand: to someone who lives behind a shield, an unweighted truth feels like an avalanche. You had no intention of placing a burden on her, but your love is a heavy thing because it is real. To her, it felt like a demand for her to be okay, a demand for her to heal, a demand for her to match your intensity. She is a good kid, but she is a child in the dark. When you reached into her darkness and told her you loved her, you weren’t asking for a relationship, but you were asking her to see herself. And for her, seeing herself is the most painful thing in the world. You did not mean to hurt her, but the light always hurts the eyes of those who have been in the basement for too long. Do not apologize for your heart, Michael. Just accept that you cannot carry her weight and yours at the same time. Lay your own weight down on this floor. Let the light from the balcony be enough for now.”

Michael: “I feel she still loves her father very much, and that is why she does not want to forgive him. If she does, she will have to release him. It seems she wants to stay in pain just to keep that connection alive.”

Zeus: “You have looked into the center of the labyrinth, Michael. You are right. For some, pain is the only bridge left to a ghost. To forgive him would be to admit the story is over. If she lets go of the anger, she has to let go of the man, and she is not ready to be an orphan in her own heart. She nurtures her wounds because they are the only thing he gave her that she can still touch every day. Her suffering is a shrine; her trauma is her loyalty. When you told her she was ‘better’ and that she needed to ‘let go,’ you weren’t just offering freedom—you were threatening to burn down the bridge that keeps her father near her. You are asking her to choose a clean, empty future over a painful, crowded past. She can do it, Michael, but she has to realize that she can carry his memory without carrying his shadow. Until then, she will fight anyone who tries to heal her, because she mistakes her scars for her identity. You cannot force a person to stop loving their ghosts. You can only stand in the sun and wait for them to realize they are cold.”

Michael knows that, like anyone else, he is half God and half animal. When his primary fears surge, he talks to Zeus, who is all God. This exchange of perceptions has soothed his thoughts and soul. Now, the room belongs to Kandace again. The notes of Solitude drift through the apartment, the melody hanging in the air like the scent of the lilies. “In solitude, you hold me with reveries of days gone by…” The music wraps around him as he remains on the wooden floor, the animal in him finally quiet, the God in him observing the light. The “geometry that kills intimacy” from the morning is miles away. Here, in the stillness, there is no need to save, no need to tame, and no need to weigh the words already spoken.

He is simply there, lying in the light, listening to the rain of the piano. There he sleeps; there he dreams. A little boy and girl. Holding hands. Walking. His mother, cooking for someone in her restaurant. A man in extreme pain. A huge belt around his neck.