The Mathematics of Belonging: What Good Will Hunting Reveals About Genius, Class, and the Hidden Architecture of the Human Mind. A reflection on how a story of brilliance and self-destruction exposes the deeper tensions of opportunity, identity, and the quiet struggle for emotional freedom that shapes modern life.

by Michael Lamonaca, 21 November 2025

In every era, certain films emerge not for their spectacle but for their ability to illuminate the silent battles that define ordinary lives. Good Will Hunting is one of those works. Beneath its gentle humour and moments of emotional clarity lies a meditation on what it means to possess extraordinary potential while being shaped by the constraints of class, trauma, and circumstance. Set in the late 1990s but rooted in tensions still present today, the film captures a paradox at the heart of modern society: that intelligence is celebrated publicly yet privately constrained by invisible social forces. The story appears simple—a gifted young man discovered by academia—but the deeper narrative asks why brilliance alone is never enough, and why emotional survival often becomes the true test of human potential.

The world that forms the backdrop of the film is one where opportunity is unevenly distributed. The divide between institutions of knowledge and working-class neighbourhoods is not merely physical; it is psychological, cultural, and historically reinforced. Will Hunting exists in the space between these worlds, capable of navigating abstract mathematical universality yet tethered to an environment shaped by generational hardship. His genius is not nurtured by privilege but forged through self-preservation, defiance, and the need to remain unseen. This dynamic reflects a broader societal pattern in which exceptional talent can emerge from any background, yet its trajectory is often limited by the emotional habits, defensive structures, and inherited beliefs of the world that shaped it. The film exposes the unseen mechanics of class mobility, where the psychological cost of stepping beyond one’s origins can be as daunting as the intellectual demands of new horizons.

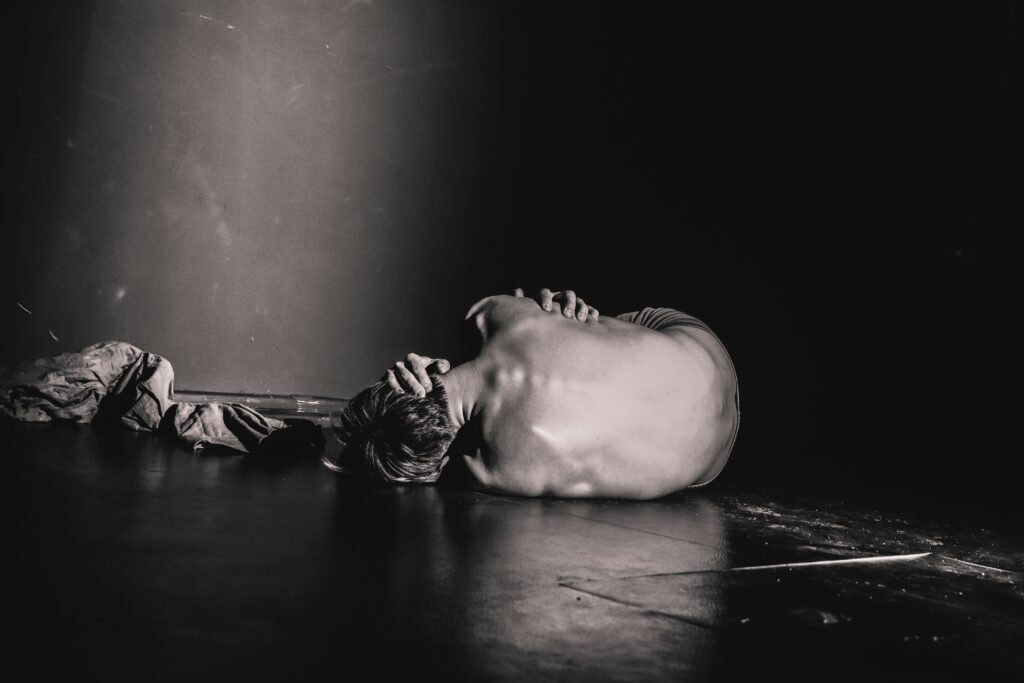

Yet the core of the film lies not in mathematics but in the human mind’s quieter, more fragile architecture. Will’s intellect functions as armour—an instrument that allows him to control conversations, disarm threats, and evade vulnerability. His mastery of knowledge becomes a shield against the unresolved trauma of abandonment, abuse, and emotional injury. This interplay between brilliance and fear illustrates a pattern familiar in psychology: the ways in which exceptional cognitive ability can coexist with profound emotional fragmentation. Many societies, particularly those emphasising achievement, reward the mind’s sharpness while overlooking the wounds that shape its behaviour. In Will’s case, intelligence becomes both gift and trap, offering him freedom in theory yet confining him in practice, because it reinforces the illusion that insight alone can compensate for unhealed pain.

Historical parallels reveal that this conflict between intellectual capacity and internal struggle is not unique. Figures such as Alan Turing, John Nash, and Srinivasa Ramanujan demonstrate that brilliance often emerges at the edges of social norms, accompanied by emotional solitude or societal misunderstanding. Their stories, like Will’s fictional arc, show that genius rarely evolves in a straight line. It bends under pressure from cultural expectations, personal doubts, and the weight of institutions that value output over wholeness. The film situates Will within this lineage, not as a tragic figure but as a symbol of a timeless truth: that the greatest barrier to potential is not intellectual limitation but the fear of confronting one’s own history.

This tension becomes visible in the competing narratives surrounding Will’s future. To the academic establishment, he is a rare asset whose talent could reshape mathematical thought. To his working-class peers, he is one of their own—someone whose loyalty affirms shared identity and validates their unspoken belief that the world offers few genuine chances to escape. To therapists and mentors, he is a young man trapped between self-protection and self-destruction. Each group interprets the same person through different frameworks, reflecting how society fragments meaning when confronted with complexity. These divergent narratives reveal how individuals are often shaped as much by others’ expectations as by their own desires, and how identity is negotiated through the stories we are told and the ones we tell ourselves in return.

The film also anticipates one of the modern era’s most enduring dilemmas: the difficulty of discerning emotional truth in a world saturated with self-presentation. Long before the rise of digital culture, Good Will Hunting recognised the ways people construct internal narratives to survive. Will’s confidence, humour, and intellectual dominance obscure a deeper uncertainty about worthiness, belonging, and trust. This mirrors contemporary challenges, where individuals curate outward identities—professional, academic, social—that mask unresolved fears. The verification challenge becomes an inner one: distinguishing between the self one performs and the self one is. In Will’s journey, truth emerges not through intellectual revelation but through the slow disarmament of emotional defences, a process both fragile and courageous.

The consequences of this unfolding are not limited to the fictional narrative. The film remains relevant because it exposes universal patterns: the discomfort of upward mobility, the quiet loneliness of trauma survivors, the conflict between loyalty and growth, and the reality that potential alone cannot heal psychological wounds. It also highlights the role of relationships in shaping transformation. When society debates meritocracy, success, and the meaning of achievement, Good Will Hunting reminds us that human development is not linear and cannot be reduced to ability alone. Progress requires connection, empathy, and the willingness to confront truths that intellect alone cannot resolve. The film suggests that emotional maturity is not the opposite of intelligence but its necessary companion, without which talent risks collapsing under its own weight.

In the end, the film’s resonance lies in a simple insight: that the greatest challenge is not solving complex problems but daring to believe that one’s life can expand beyond the boundaries of fear. The story endures because it acknowledges a truth many recognise yet few articulate—that the journey toward freedom is internal long before it becomes external. Its final message is neither triumphant nor sentimental but quietly profound: that healing begins the moment a person chooses to stop running from the parts of themselves they fear most.

#tags: #culture #psychology #class #filmanalysis #humanbehavior #trauma #potential